Stress, poverty and disease are tightly linked according to Robert Sapolsky. His article in the December 2005 issue of Scientific American substantiates that there is a 10 fold increase risk for some diseases that can be attributed to the stress of being poor. That stress, apparently is exacerbated by the perception of poverty that is heightened in societies with wide income gaps, such as the U.S.. Studies cited (Michael G. Marmot of the University College London) in the text of the article debunk the idea that its simply lack of access to care and unhealthy lifestyles that are at the root of the disparities in health.

Interesting reading material suggested by the article include the following:

Mind the Gap: Hierarchies, Health and Human Evolution by Richard Wilkinson, Wiedenfeld and Nicolson 2000.

The Health of Nations: Why Inequality is Harmful to Your Health. Ichiro Kawachi and Bruce P. Kennedy 2002.

The Status Sydrome by Michael Marmot 2004.

Why Zebras Don't get Ulcers: A Guide to Stress-Related Diseases and Coping. Robert Sapolsky, 2004.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Saturday, October 15, 2005

We've been doing experiments with depleted Uranium at the lab and I've beens surprised at how little is known about it, especially as a toxic chemical. I wrote the following letter to Science News in response to a recent article on the low-level of radiological risk of the material.

Editor, Science News

1719 N Street, N.W.

Washington D.C. 20036

Your article on the hazards of depleted Uranium (SN: 8/13/05, p.110) should not lull us into believing that depleted Uranium is a low risk material, especially for children who may later play on the battlefields of the current war. While, I applaud Mr. Marshall for using scenarios such as that of children playing in and around vehicles destroyed by depleted-uranium munitions in his radiological risk analysis, he, and others, fails to consider potential chemical effects that uranium may share with other heavy metals, such as lead. There is a rich body of literature documenting the deleterious effects (e.g. lowering IQ) of lead on children, even at doses below those considered acceptable by CDC guidelines. Little if anything, however, is known about the effects of uranium on the developing nervous system, leaving open the question of whether or not it affects children who might inhale uranium-contaminated dust or be exposed to it in food or water. Given the state of our ignorance it is important for uranium to be evaluated beyond its radiological effects as “a major player, in causing health effects,” especially where the well-being of children is concerned.

Editor, Science News

1719 N Street, N.W.

Washington D.C. 20036

Your article on the hazards of depleted Uranium (SN: 8/13/05, p.110) should not lull us into believing that depleted Uranium is a low risk material, especially for children who may later play on the battlefields of the current war. While, I applaud Mr. Marshall for using scenarios such as that of children playing in and around vehicles destroyed by depleted-uranium munitions in his radiological risk analysis, he, and others, fails to consider potential chemical effects that uranium may share with other heavy metals, such as lead. There is a rich body of literature documenting the deleterious effects (e.g. lowering IQ) of lead on children, even at doses below those considered acceptable by CDC guidelines. Little if anything, however, is known about the effects of uranium on the developing nervous system, leaving open the question of whether or not it affects children who might inhale uranium-contaminated dust or be exposed to it in food or water. Given the state of our ignorance it is important for uranium to be evaluated beyond its radiological effects as “a major player, in causing health effects,” especially where the well-being of children is concerned.

Friday, October 14, 2005

Here is my studio in progess. I recently repainted the wall and now I want to make some book shelves, but this gives you a sense of what it looks like in the tiny space I dedicate to painting.

My most recently completed painting is titled,

"The shape they should have been." The drawings of the rib cages were taken from a health text that I was recently given by relatives in Vermont. My great grandmother Shanley was a nurse, and her daughter Mary graduated from UVM medical school in 1938, the only woman in her class. The other, more abstract shape, is taken from a fabric collage I made while I was in graduate school in Iowa.

Monday, October 03, 2005

It's been a busy month, with interviews accross the state from Buffalo to Rochester, and then Vermont. This has not left much free time for painting or writing blogs. While in Vermont, I stayed at Anne Rowley's house, where her sons still run a dairy farm with about 400 holsteins according to Margaret. Margaret and Anne let me sort throughthe old books that were taken from the Milton farm, that so far no one else has wanted. The books included Helen Shanley's nursing books from the turn of the century, including histology, and a slim volume from the late 1800's on writing prescriptions in Latin--Humpf! No more.

The most precious text though was on the subject of law. The title was Roman Civil law, and the date printed in Roman numerals is 1724. The typeface has "s"'s that look like f's to me. It is very old. I have been looking at these books, and already have taken images from one book: pair of pictures of ribcages, and placed it in a new painting. One set of ribs is of a woman whose ribs were deformed by the use of laces and some sort of corset; the other set is normal. What a contrast. The descriptions of what happens to the internal organs is rather graphic and discourages such practices. Now, if we could just free our minds from the assault of modern advertisements that teach us to loath the natural shape of our bodies, we might terminate the practices that enslave our bodies and our pocketbooks for all time.

I was struck recently by a magazine article that I read on tummy tucks while getting my hair cut. Not being used to reading such magazines, I felt rather shocked by it--I know I'm out of touch with the popular culture by and large, but still.... It's awful to think that people today are still spending vast sums of money to make themselves over physically in to conform to popular notions of beauty. We haven't learned much of anything it seems in the last 200 years.

The most precious text though was on the subject of law. The title was Roman Civil law, and the date printed in Roman numerals is 1724. The typeface has "s"'s that look like f's to me. It is very old. I have been looking at these books, and already have taken images from one book: pair of pictures of ribcages, and placed it in a new painting. One set of ribs is of a woman whose ribs were deformed by the use of laces and some sort of corset; the other set is normal. What a contrast. The descriptions of what happens to the internal organs is rather graphic and discourages such practices. Now, if we could just free our minds from the assault of modern advertisements that teach us to loath the natural shape of our bodies, we might terminate the practices that enslave our bodies and our pocketbooks for all time.

I was struck recently by a magazine article that I read on tummy tucks while getting my hair cut. Not being used to reading such magazines, I felt rather shocked by it--I know I'm out of touch with the popular culture by and large, but still.... It's awful to think that people today are still spending vast sums of money to make themselves over physically in to conform to popular notions of beauty. We haven't learned much of anything it seems in the last 200 years.

Sunday, September 11, 2005

Isabel and her Kindergarten artwork inspired this painting. Isabel did a series of pencil drawings in Kindergarten, which I absolutely loved, and made into a small book over the summer. I traced some of the words and images into this painting and juktaposed an pictures of her from June when she was picking cherries in the back yard. Isabel says she looks sick in it, but I imagine when she's older, she may grow to like it. Or, perhaps she'll be an accomplished portrait artist and decide to burn it. I don't know how many more paintings I'll do with figures; they are a special challenge for someone who has mostly worked with abstractions.

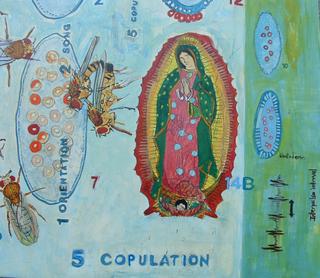

The Virgin of the Flies, another painting inspired by Drosophila Melanogaster and my childhood in Mexico, where the Virgin of Guadalupe is a virtual obsession. Forgive my indiscretion with your Madonna, she just had to be in this painting. This painting was inspired by images of the fruitfly embryogenesis, which has some unique features. One interesting thing is that the embryo has a stage in which the nuclei divide, but the cells do not differentiate until there have been 8 or more divisions. Thus the embryo has a distinctive appearance. The adult flies in this painting are shown going through several of the stages of Drosophila courtship, which include a period when the adult male sings to his prospective partner while holding one of his wings out to the side.

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

I'm in Buffalo with Celia While, my poet friend and I'm having a really good time catching up with her. It's been two years since I've seen her, since Calvin was born. Tonight is my first night away from him, and I thought I would feel really strange, but what I feel is really free. I hope Dave is having an o.k. time. Dave will have his turn this weekend when he goes to Adam's batchelor's party at Cold River. At any rate, I am surprised at how good it feels to be in Buffalo. I could totally see myself here living in a house near Elmwood. We'd have a great time. So, here's hoping it's an option.

More later...

More later...

Thursday, August 11, 2005

The Thousand Word Version of the "Describe Yourself"

My name is Sarah Averill. I am thirty-four years old. I am married and have two children: Isabel Aster Ella and Calvin Merriwether. We live in Albany New York where we keep a house with a crazy overgrown garden where the kids can pick strawberries, snow peas, and black raspberries in season. The neighbor kids sometimes cut through and help themselves. That’s why we planted so many. I like this urban life with corners that keep me connected to my family’s more rural roots.

I was born in Bangor, Maine to the son of a paper-mill hand, and the daughter of a failed Vermont dairy farmer turned apple peddler. Both of my parents became professionals, my mother a doctor and my father a lawyer. Both remained connected to their more humble origins, and taught me to respect people no matter what their social class or financial means.

These values were reinforced by my education at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations and by my experience living at Telluride House, an eccentric institution that offered room and board scholarships to students dedicated to democratic values. While at Cornell I was influenced by the writings of John Rawls, particularly his book A Theory of Justice.

I have an older brother named Patrick and a younger sister named Leah. When she was little she was my tagalong. Excepting the senior prom, she went everywhere with me. At the time I thought nothing of it; it didn’t occur to me to resent it, and now I wonder if it may have kept me out of trouble as a teenager. We lived in Mexico from the time I was in first grade until fourth grade, so I learned to read and write in Spanish. This put something of a crimp in my education: I never did learn to spell English very well, and I have a terrible weakness for Mexican Mariachi music.

I like to sing with my husband and now we are teaching the children traditional songs and sea shanties. He comes from a long line of landlubbers so I don’t know why he so loves the music of the sea. As far as I can tell the only thing he shares with sailors is a certain trepidation about swimming. I, on the other hand, come from a long line of swimmers, but I don’t know of any sailors in my family tree either. I sing along just to keep him company. And it’s such fun to hear Isabel and Calvin piping in too. What will they become when they grow up?

If you were to ask me what I felt my greatest accomplishment in life was so far, I’d have to say being happily married for going on ten years. After that I would add that I’ve found a community and become part of it by participating in the local organizations from the neighborhood association to the school PTA. These are not things that I can put on a resume, but for me this community is what has made other accomplishments possible.

My greatest fear is of dying without getting to finish raising my children. They are my greatest love and my greatest inspiration in this life so far. When I tell people I am going to medical school they have one or two reactions: “Go for it!” and/or, “Who will raise your children?”

My answer is that, just as I do now, I will continue raising them with help from my husband and the community that I have been fortunate to find and build on over the last few years here in Albany. I know I will have less time to paint, and write, and garden, and sing. I know I may miss some of the major events of my children’s lives. This is the compromise that I’ve made in order to follow my path and usher them along theirs

My greatest hope is that I will leave the world a better place for my children and those that come after them. For me becoming a physician is a way of making this hope a reality. I know intimately that the world is in terrible trouble and that there are a lot of reasons to despair. Refraining from cynicism is as close to a religious practice as I have.

June 15, 2005

Dear Margaret,

It pleased me; the way you appeared, as if from nowhere, quietly at my back door, like an old friend just stopping in from down the street. How I wish you lived closer and could do just that. You are like a sister to me now; a chain to the past and other half of the stories that I grew up on; a rope that pulls me into the future, more whole and more sane than I’d be without you. And, in some ways, you are a mirror, too, telling me who I am. In the reflection from the gnarled surface of the family that stayed in place, I am becoming more solid. There is substance where once I felt only the wind, the hollow vacuum of un-belonging to place, to community, to family, to history. I am putting down roots in this new place, where I am finally becoming, and becoming, and becoming…

I have pictures of you in the yard, perched on Calvin’s Little Tykes chair, like a farmer on a three-legged stool, with the foxgloves just beginning to bloom behind you. You are lovely, and at home, on my small fifty-by-thirty-foot plot, peeling apples from the hand-made ash basket you brought from Westfield. There are still a few apples in the basket, which now sits on the floor in my kitchen, next to the refrigerator. They have been kept too warm by the heat it gives off this time of year, and have begun to take on the sweet, waxyness of apples in autumn. It is the odor of your Uncle Patrick’s (my grandfather’s) truck, the smell of my murky childhood. I will always associate that smell with him and the mysteries of our family’s schism from the Vermont Rowley clan.

How strange and wonderful that we should have become friends these fifty-odd years after his exile. I have such a hard time attending to the demands of my immediate family, complicated by the alienation, passed on generation-to-generation, stemming from Pat’s irreverant, innatention to the collective family aspirations. What they were, we keep wondering, and characterizing, even scoffing in our ignorance, even as it diminishes with added details. Did they really want a dairy farming empire in Milton? What really drove them? How much did the girls really contribute to the farmland purchases for the men? Were there others who wanted to get out from under the matriarch? Did they get out, get away from the dominion of Helen Rowley, or did she continue to dominate them even from the grave? And what about him, Helen’s husband, Pat’s father? Who was he other than a state senator? How shamed was he by his son’s record of mischievous misdeeds, and then unfortunate transaction, that landed him in jail, with a cold shoulder from the exhasperated family? What did grandpa Pat’s father think? I never hear about him.

How much/many of the truth/s will come out? Does it even matter anymore? Somehow, I keep wanting to pry open the past, even as I find the present unbearable—Pat’s trangression’s did not stop when he left Vermont, collecting his children and wife from the places they sheltered during his stint in jail for selling the cows. Things may have been easier if his story had stopped there, but it was just the beginning of a series of dislocating events. Now, I wonder if any of it matters. It does. It does, I know, but I’d like sometimes to think that it might not.

When I was a kid, I loved climbing up into the attic at 618 S, Beech Street, where Pat and his wife, Mazel, my mother’s mother, ended up living when my mother headed off to medical school in Mexico, aspiring to physicianhood, like the children of aunt’s and uncles that remained true to the clan. When Mazel’s mother moved in with her from Vermont, after her husband Ralph died, there were lots of boxes of old things, china, cufflinks, hatpins, stacked, and sorted, then as the years passed, picked over, and disorganized-- probably nothing valuable, but they had a certain allure, just because they were old, and they were in the attic, where the light is strange, and even the dust is romantic.

Now, I don’t think I’d think much of the odd assortment, just the sorts of things you’d see at any ordinary rummage sale. Everything valuable had long since been sold. I wonder, if the whole mess with Pat will seem like that in a few years, as the last of the siblings involved in the conflict pass away, and only the cousins remain—1st and 1st, once removed; will it all seem dusty and boring, even downright plebian, like a tired Sunday diatribe—just another American family with an old horse to beat.

Perhaps we can open our mouths in merriment and let the flood of emotion pent up too long run like the spring snow melt, clear over the cobbles, just smoothing them a bit in gentle eddies of song and scented seasons.

Love,

Thursday, July 21, 2005

In May I submitted a letter to the editor to the Times Union about walking vs. driving Isabel to school. It was a very interesting experience for me to have my neighbors read it, comment to me about it, and even read it at the PTA meeting in my absence. I later learned that by writing this letter some people had actually changed their behavior; they decided to walk their kids to school from the neighborhood, or if they were coming from farther away, to get out of their cars and walk their kids inside the school to greet the teacher in the classroom. This is, I hope, the first of many such efforts.

Tuesday, July 19, 2005

Thursday, July 14, 2005

The milkweed was just getting ready to bloom on the weekend of July 4th. I can still remember the first time I noticed milkweed as a flower. It was the summer I turned 12. I was taken by how sweet it smells. And then I noticed the intricate blooms. This particular plant had a nice bend in the stem, lending additional grace to the plant.

Tuesday, July 12, 2005

Monday, July 11, 2005

For this I believe

I believe in kitchen-table democracy. I believe in small “d” democracy, the kind where parents sit around the table and argue with each other about which candidate they should vote for, the kind when mothers gripe together about the schools not being good enough and plot to start new ones, or they talk to their kids about the Constitution and what it means. I believe in small “d” democratic institutions: PTA's, school boards, neighborhood associations, and the League of Women Voters. I believe in the kind of democracy you can take out on the street, the kind that gets you talking to your neighbors up and down the block and strangers across town too, the kind that gets kids excited and involved enough to get into the voting booth with you and learn to pull the lever.

Last night I attended the last PTA meeting of the year at my daughter’s elementary school, the Albany School of Humanities, on Whitehall Road in Albany, New York. At that meeting, I spoke on the need to allow the child acting as master of ceremonies at the end-of-year variety show to say, “Them was good,” without having her grammar “corrected” by the adults coordinating the program. Another parent at the PTA, felt that such ungrammatical speech was a poor reflection on the child, the school, and the PTA, which sponsored the program. Certainly, I argued, there is a place for proper, grammatical, speech, but so too is there a need to create a place for speech that reflects ethnic background, the popular culture, the culture of youth, and creative use of language, especially in a school community that is diverse, with children from over a dozen countries. Discussion ensued for some time, and ultimately, there was general agreement that children need to learn both, and to distinguish when to use each kind of speech to best effect.

Walking home from the meeting, hanging onto my two-year-old son, with my husband, carrying our five year-old daughter, soon to be Kindergarten graduate, on his shoulders. I felt like a true member of a community, with valuable democratic institutions. The PTA is not democracy with a big “D”, but with a small “d”, the kind I’d learned about as a teenager from parents who took the time to involve me and my peers in public meetings on educational issues that affected us.

One woman, Alison Des Forges, who has since gone on to receive a McArthur genius award for her work with Africa Watch, stands out in my mind. Her high-profile efforts at the UN have been recognized, but perhaps she should also know about the impact she had on those of us she taught the lessons of democracy with a little “d." Alison Des Forges helped me and a group of my peers, when we were just high-school freshmen, to attend a public hearing on an effort to ban several books from the Buffalo School district library.

I don’t remember the details of the objections to the book. They don’t matter now. What matters is that she initiated us into the realm of public participation in decision-making. She led us, with the U.S. Constitution as a backdrop, into the practical realm where decisions are made. She facilitated an opportunity for us to speak in public, be heard in our own communities, and then beyond when our speeches were published in the Humanist Magazine. While we may not have influenced the outcome of the meeting, she gave us our first glimpse at the inner workings of decision-making institutions at the community level, where decisions are made that impact our daily lives and the lives of our children. She showed us that to care is to be involved.

This was a critical rite of passage for me. As a parent now, taking my five-year-old daughter to public meetings, and into the voting booth with me, I realize the significance of being involved from childhood in democratic decision making. She laid the foundation for me to find a voice, the courage to speak, and the practical know-how of getting involved.

Until the meeting last night, I hadn’t reflected much on where I’d learned to speak out and express my opinions at a public meeting. I became even more grateful to Alison Des Forges' kitchen table, a neighborhood meeting place, a small “d” democratic institution, where I learned about little “d” democracy. We must each, when it is our turn, take it out into the world, but I believe –- as Alison showed me -- that democracy begins at home.

I believe in kitchen-table democracy. I believe in small “d” democracy, the kind where parents sit around the table and argue with each other about which candidate they should vote for, the kind when mothers gripe together about the schools not being good enough and plot to start new ones, or they talk to their kids about the Constitution and what it means. I believe in small “d” democratic institutions: PTA's, school boards, neighborhood associations, and the League of Women Voters. I believe in the kind of democracy you can take out on the street, the kind that gets you talking to your neighbors up and down the block and strangers across town too, the kind that gets kids excited and involved enough to get into the voting booth with you and learn to pull the lever.

Last night I attended the last PTA meeting of the year at my daughter’s elementary school, the Albany School of Humanities, on Whitehall Road in Albany, New York. At that meeting, I spoke on the need to allow the child acting as master of ceremonies at the end-of-year variety show to say, “Them was good,” without having her grammar “corrected” by the adults coordinating the program. Another parent at the PTA, felt that such ungrammatical speech was a poor reflection on the child, the school, and the PTA, which sponsored the program. Certainly, I argued, there is a place for proper, grammatical, speech, but so too is there a need to create a place for speech that reflects ethnic background, the popular culture, the culture of youth, and creative use of language, especially in a school community that is diverse, with children from over a dozen countries. Discussion ensued for some time, and ultimately, there was general agreement that children need to learn both, and to distinguish when to use each kind of speech to best effect.

Walking home from the meeting, hanging onto my two-year-old son, with my husband, carrying our five year-old daughter, soon to be Kindergarten graduate, on his shoulders. I felt like a true member of a community, with valuable democratic institutions. The PTA is not democracy with a big “D”, but with a small “d”, the kind I’d learned about as a teenager from parents who took the time to involve me and my peers in public meetings on educational issues that affected us.

One woman, Alison Des Forges, who has since gone on to receive a McArthur genius award for her work with Africa Watch, stands out in my mind. Her high-profile efforts at the UN have been recognized, but perhaps she should also know about the impact she had on those of us she taught the lessons of democracy with a little “d." Alison Des Forges helped me and a group of my peers, when we were just high-school freshmen, to attend a public hearing on an effort to ban several books from the Buffalo School district library.

I don’t remember the details of the objections to the book. They don’t matter now. What matters is that she initiated us into the realm of public participation in decision-making. She led us, with the U.S. Constitution as a backdrop, into the practical realm where decisions are made. She facilitated an opportunity for us to speak in public, be heard in our own communities, and then beyond when our speeches were published in the Humanist Magazine. While we may not have influenced the outcome of the meeting, she gave us our first glimpse at the inner workings of decision-making institutions at the community level, where decisions are made that impact our daily lives and the lives of our children. She showed us that to care is to be involved.

This was a critical rite of passage for me. As a parent now, taking my five-year-old daughter to public meetings, and into the voting booth with me, I realize the significance of being involved from childhood in democratic decision making. She laid the foundation for me to find a voice, the courage to speak, and the practical know-how of getting involved.

Until the meeting last night, I hadn’t reflected much on where I’d learned to speak out and express my opinions at a public meeting. I became even more grateful to Alison Des Forges' kitchen table, a neighborhood meeting place, a small “d” democratic institution, where I learned about little “d” democracy. We must each, when it is our turn, take it out into the world, but I believe –- as Alison showed me -- that democracy begins at home.

Recent photos from this year's garden. On the left is a bleeding heart in May. I particularly liked that you could see this flower from both the front and the side at the same time because of the way the three are pivoting in space.

On the left is a lily that is mixed in with the leaves of several other plants that have contrasting textures" Bee Balm, vetch and the lily leaves themselves. There is a house (?) fly on one of the petals that was walking back and forth along the flower for some minutes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)